[vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”sidebar-sidebar-reviews”]

[vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”sidebar-sidebar-reviews”]

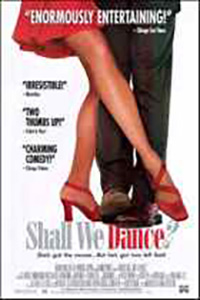

Shall We Dance

Japan (1996), 136 minutes

Shall We Dance is a film with many levels. Its great fun, its one of the most innocent and sweet movies Ive ever seen, it gives us real insight into areas of Japanese culture that are usually repressed, and it tells us how we all, in one way or another, have hidden desires and/or dreams that most dont have the courage to live out.This story is about Shohei Sugiyama (very well played by Koji Yakusyo), a hard working family man who appears to have a perfect “Leave it to Beaver life: he rises early, takes the train to work, comes home late, talks a bit to his wife and daughter, sleeps, and repeats the process again and again. Old shows like “Leave it to Beaver and “Father Knows Best projected a mentality that the powers that be (in the USA and elsewhere) so wanted us to fall in line with: follow the rules, never do anything that will rock the boat, accept cultural brainwashing as a positive part of life, hide from real individuality, and immerse yourself in a world devoid of color and energy. This is what Mr. Shohei faces, and the movie revolves around his efforts to step beyond the cultural boundaries placed upon him.

In American film, virtually all movies are either action/special effects/sexuality based, or harp upon such clichés as: “love conquers all and “family is everything. Apparently a deeper and more honest look into the human psyche will never be embraced by the big studios. Shall We Dance, though, takes us on a serious and extremely funny inner journey in a way I wouldnt have thought possible: there are no sex scenes (implied sexual feelings, yes, but an honest look in the mirror wouldnt be possible without this), there is no violence, there are no special effects, and there isnt any frenetic action. Instead, we get complicated characters filled with dignity and depth, love as seen in the guise of long distance fantasy (Everyone has seen someone from afar and felt tinges of desire, all the while knowing that the object of this love had nothing to do with a person; instead, it represents our own very personal longings and dreams.), and courage as defined by a person daring to try to become more than he is, to the ultimate betterment of all those around him.All of these things come to life via the artistic backdrop of ballroom dance, something one wouldnt imagine in a Japanese film. Allow me to quote from the film itself: “In Japan, ballroom dance is regarded with much suspicion. In a country where married couples dont go out arm in arm, much less say I love you out loud, intuitive understanding is everything. The idea that a husband and wife should embrace and dance in front of others is beyond embarrassing. However, to go out dancing with someone else would be misunderstood and prove more shameful. Nonetheless, even for Japanese people, there is a secret wonder about the joys that dance can bring. This incredible film does the impossible by exploring all the things just mentioned, while never regressing into sentimentality. It remains true to itself to the last, sweet drop by dragging you into the minds of the characters. You actually feel their depression, you understand the family problems because youve lived them yourself, you want Mr. Shohei to step past the path often tread because you have always wanted to do this yourself; and you feel the characters exaltation when they all embrace that missing part of themselves.