[vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”sidebar-sidebar-reviews”]

[vc_widget_sidebar sidebar_id=”sidebar-sidebar-reviews”]

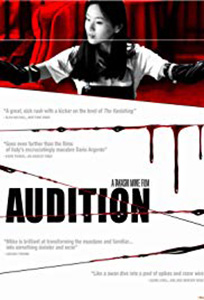

Audition

Japan (1999), 115 minutes

Audition is a gorgeously photographed movie, with striking camera angles, a sensuous use of color, and numerous shots composed and framed as carefully as a Hokusai woodcut of Mount Fuji. And this masterful cinematography is complemented by equally masterful editing. Miike surprises us again and again with sudden, unexpected cuts from one scene to another. He also likes to alternate slow, peaceful scenes in which a character sits or stands in silence, lost in thought, with rocketship scenes featuring hyperkinetic music and a frantic, rapid-fire sequence of quick cuts.

Two of these quick-cut scenes deserve special praise. Either could stand by itself, one as a humorous short-short story, the other as a poem of nightmarish delirium. The first scene shows us 30 actresses auditioning, one by one, for a part in a movie. The cuts are so rapid that we only get to see each actress do her stuff for a few seconds, but each bit is nicely crafted to be amusing in a different way, with a complicated accumulative effect that’s primarily comic with strong undercurrents of pathos and satire. The second scene comes after the protagonist drinks drugged whiskey, blacks out, and falls to the floor. What we see for the next few minutes is a surreal phantasmagoria of events that the protagonist knows have already happened intermixed with unspeakable possibilities. Once again, Miikes quick cuts greatly enhance the effect created by this sudden onslaught of imagined horrors. Rather than building slowly, the scene comes at us like a lunatic with a syringe.

Music defines the mood sweetly melancholy music for sentimental scenes, sinister music for scenes of ominous foreshadowing, romantic music for love scenes, and spritely music for comic scenes. This technical aspect of Audition is too obvious, too blatantly manipulative in its attempt to direct our emotions. Perhaps this criticism merely reveals my personal taste. I prefer movie music that challenges or complicates my emotional reaction to what I’m seeing on the screen.Equally obvious is the fashion in which every element in many of the scenes has been carefully contrived to convey a particular theme or symbol. This contrivance can be seen, for example, in the all-too-frequent use of coincidences. During a fishing scene, the father and the son are discussing women when the father remarks metaphorically that in his search for a new wife, he wants to catch a big fish. Sure enough, a minute later his line goes taut, his pole bends forward, and he reels in a whopper. What a coincidence! How symbolic!

In another scene the father has a stack of thirty resumes fanned out on his desk and is about to look through them one by one when he accidentally spills a few drops of coffee on the corner of a resume that’s near the bottom. He wipes off the coffee, then pulls the resume out of the stack and looks at the photo on it. You guessed it. By chance this happens to be the resume of the actress he falls for. How coincidental!